A light hammock of lace – an artifact of Warao origin – is laid out in front of the speakers’ desk. The hall is the auditorium of the Consolata missionaries’ house in Rome, a beautiful but sober residence a few hundred meters away from the dome of St. Peter’s and right next to the Urbaniana University. The occasion is a conference taking place simultaneously with the missionary month (October) and above all the Pan-Amazonian Synod. “The faces of the ad Gentes” is the title that was chosen. Perhaps it is a bit of a cacophony but, if one re-reads it well, the term “faces” is the most attractive part and certainly the newest.

The question arises (almost) spontaneously: who is behind these faces? We could easily see many people behind there: maybe those who sleep in makeshift beds around the Vatican. Or maybe those represented in the monument to the migrants which, for a few weeks now, one can see to the side of Bernini’s colonnades: a black spot (strictly speaking but also in a broad sense) next to the pure white of the columns. This time, at least this time, it is the traits of the indigenous peoples that are to be found in those faces. Of the Amazon region, but not only of the Amazon.

At the foot of the speakers’ table, the Consolata Missionaries (Sisters, Brothers and Fathers) have thus placed symbols of Catrimani (Brazil), Raposa Serra do Sol (Brazil again), Orinoco Delta (Venezuela) and Argentina; but also of Africa (Guinea Bissau, Kenya) and Asia (Mongolia).

After presentations and greetings, the first intervention was by Luis Ventura, a lay missionary, anthropologist and person in charge of the CIMI in Boa Vista (Roraima, Brazil). In his speech he recounted the difficult relationship between (white) states and indigenous peoples. The former try to impose an integrationist political line (in short, the attempt to nullify ethnic and anthropological differences at the stroke of a pen) with a single, more or less obvious objective: to apply without interference the devastating but profitable extraction-based model that is in vogue in Latin American countries. For their part, indigenous peoples have long since learned to fight tooth and nail for their constituent features, which can be summarize in three terms: diversity, ancestral territory, collective rights. Ventura then focused on Brazil and the anti-indigenous tsunami caused by the rise to power of Jair Bolsonaro, in January 2019.

In his speech, Lirio Girardi, a Brazilian missionary, stated that the most historically and anthropologically significant change occurred with the Second Vatican Council. From that moment on, missionaries released that, in the unequal conflict between maloca and fazenda, they had to side with indigenous peoples. In choosing so, they were aware they could have been suffering criticism and offenses (if not threats) from the white population, as in fact it happened at the time of the recognition of the Indigenous land Raposa Serra do Sol.

After Latin America, the African continent closed the first day of the conference. The words of Sister Anelia Gomez gave room to the 30 indigenous peoples (among them, the Balanta and the Pelep) of Guinea Bissau.

Beautiful, exotic and above all mysterious, the Huaorani are one of those indigenous peoples that photographers and tourists crave for. This was recalled – with concern – by Father Lino Tagliani who, for five years, shared their life in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador. Some of the Huaorani communities are still uncontacted, but even those contaminated by white society have not given up their world. Not even the spears that in 1987 pierced Mgr. Alejandro Labaka and Sister Inés Arango.

The Conference “The faces of the ad Gentes” then continued its search for similarities among indigenous peoples of “other Amazonas”. This led the participants to Africa and specifically to Kenya, a country in which – just like in Ecuador – there is no shortage of spears. The Samburu people is the best known among Kenyan ethnic groups for being a warrior people, as Father James Lengarin – a Kenyan missionary and Samburu himself – said. “We are warriors for the community,” he explained. “Among our indigenous peoples the community always prevails over individuality and competition. For this reason, for a foreigner, and for a missionary in particular, listening becomes essential”.

Listen: a verb that came from all the working groups formed in the afternoon. “Because touching other cultures is dangerous”, but also “because the word to follow must be polyphony”.

In the evening, the Conference of the Consolata Fathers and Sisters moved to the church of the Transpontina, in via della Conciliazione.

In these days, the church of the Transpontina has been transformed into the Amazonian Common Home. Meetings and debates are hosted there. And, inside it, there is also a photographic exhibition. It is small and a bit modest, to be honest, but the main exhibition has been set up in the Vatican Museums and will display indigenous objects mostly offered by the Consolata missionaries (that work in 6 of the 9 Amazon countries).

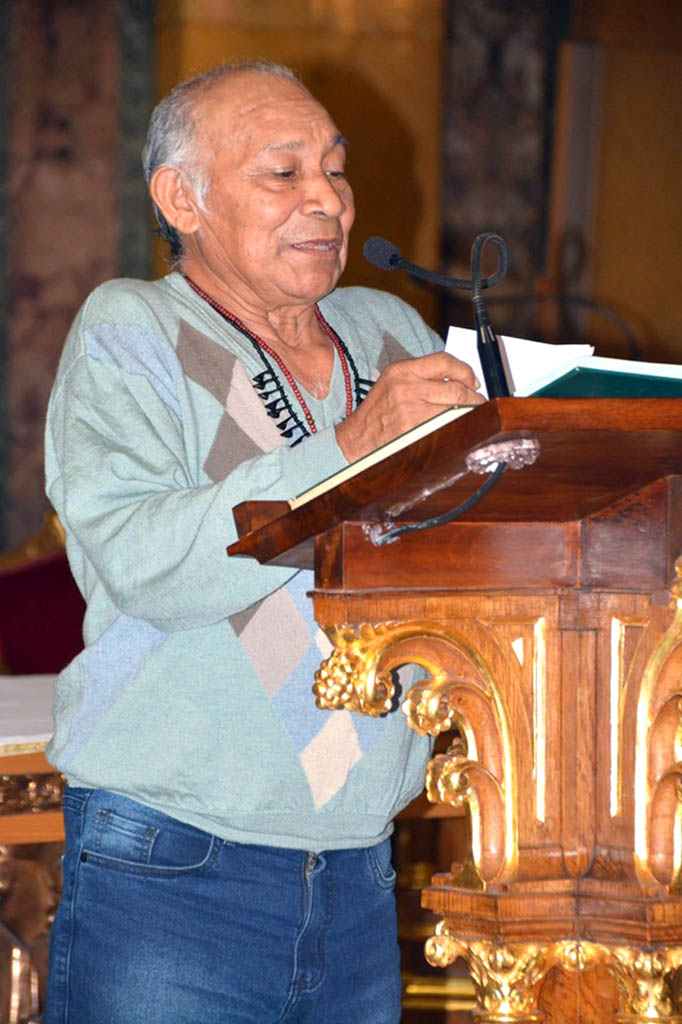

In the church, eight people took turns at the microphone to present their experience to the public. And then the time has come for Onorato Lopes, indigenous Sateré-Mawé of Parintins (Brazil). A professor and a catechist, Onorato thanked the Catholic Church for having safeguarded the spirituality of its people. And he ended with a joke that caused a general laugh: “I am so grateful that I would like to take two fathers with me.”

In the evening, around St. Peter’s Square and Via della Conciliazione, another world comes to light: that of the homeless. Many – in a number that a person could hardly imagine – lay out blankets and cardboard beds along Bernini’s external colonnade. Or under the arcades. Or in any place that can be a shelter. They come here because the police let them stay and the very presence of police patrols keeps potential attackers away. Then, around nine in the evening, small groups of volunteers bring them also a hot meal. The words that Father Giorgio Marengo – a missionary in Mongolia – said during the round table become true for them, too, at least for a moment: “The clouds pass, the sky remains”.

On the following day, the fourth day of the Symposium, many compelling inputs came at the work groups. Fathers and sisters said, among other things: “The context has shaped us”; “With their lifestyle, their culture, their cosmogony, indigenous peoples have enriched us”; “We must accept the other as it is”; “We have learned to have a vision of the Earth as life and not as exploitation”; “We were sent not to convert, but to share our beliefs.”

The main speakers, Luca Pandolfi, a priest, an anthropologist and a professor at the Urban University, and Francesco Remotti, an anthropologist and a former professor at the University of Turin, helped in finding and building unifying threads. Other anthropologists and missionary-anthropologists were attending in the auditorium hall.

Missionary sisters and fathers managed to make a fruitful exercise in self-criticism and, at the same time, to reduce self-satisfaction to a minimum. Father Stefano Camerlengo, the Superior General of the Consolata Missionaries, wisely remarked: “Humility is the most important thing”.

Paolo Moiola

[original article edited for our website]

* Paolo Moiola is a journalist and editor at Missioni Consolata Magazine, Italy.